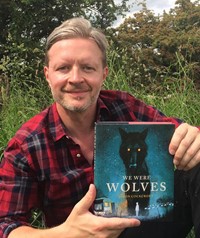

Jason Cockcroft

About Author

Jason Cockcroft was born in New Zealand and raised in Leeds, West Yorkshire. He graduated from Falmouth School of Art and is the illustrator and author of over 40 books for children, including the illustrated covers for the last three books in the Harry Potter series. Jason won the inaugural Blue Peter Book Award and has been nominated for the Kate Greenaway Medal.

Author link

https://www.thelittleyellowbird.co.uk/;

Interview

We Were Wolves (Andersen Press)

May 2021

We Were Wolves is a taut, powerful novel about family and love, loss and forgiveness. The novel follows Boy, who lives with his father in a caravan in the woods. But his father suffers from PTSD and dark forces are circling... people who could destroy their lives.

Jason Cockcroft tells us more about We Were Wolves:

Q&A with Jason Cockcroft

1. You're known for your illustrations and your picture books; what inspired you to write a YA novel?

I've always written. Illustration has provided me with an income, so it necessarily took priority professionally, but in the last 15 years I've probably shared my time equally between writing and illustration.

I began wanting to be a comic illustrator and writer, and so the importance of visual storytelling has been fundamental to whatever I've worked on over the years, but I love literature. I don't submit my writing often, and I try to keep my fiction and my illustration as separate as possible, but there's hardly any time when I'm not working on a novel or short story.

We Were Wolves was a small personal story, and I wrote it fairly quickly. I submitted it fully expecting no-one to like or understand it, but thankfully it seemed to connect with a few publishers.

2. Can you tell us a little about We Were Wolves?

We Were Wolves is about a boy who lives with his father in an abandoned caravan in the woods in Yorkshire. His father, John, is suffering from PTSD and the boy tries to care for him, whilst also navigating the difficult terrain of his own life. They live off the land and are inspired by a complex mythology that John has developed that mixes in a sense of the ancient forests, ecology and the poetry of William Blake.

It's an unanchored, fragile sort of life, and eventually the outside world and its dangers intrude upon the woods, and drags them both into violent confrontation with a local gangster. But at the heart of the story is the love between the boy and his father, and how complicated that can be when mental health issues come into play.

3. Why did you want to focus on a boy's relationship with his father?

All fiction is fundamentally about relationships, whether it's the relationships between lovers or friends or parents and children. The relationships we develop with our parents become the models for all subsequent relationships, whether we like it or not. They are also probably the most mysterious relationships we'll ever have because as a child we're always at a disadvantage - in that we can only ever know our mother and father since they adopted the role of a parent. If we're lucky enough to have parents, and know them, we still have no sense of their lives before we were born. We can't.

As children, growing up, we project power and certainty onto our parents. They represent the adult world, and we want to know how that world works, so we trust that our parents understand the rules, and they will keep us safe. So what happens when, rather than a source of safety, a parent proves to be a source of danger? And, of course, when you're older, you realise how helpless adults can be, how fragile, how damaged, how in need of care themselves.

We like to think the adult world is rational, but it's ruled by emotion and can be chaotic, especially if you have a parent with mental health problems. My own father was very down to earth, a very simple, uncomplicated man who was satisfied with his life and who we was. He was a good father, but I fought with him when I was young, and it was only when I was much older that I grew closer to him and began to understand him better, and was able to love him. He died ten, years ago, and his death had an enormous impact on me, and changed my life, and it changed my family, too.

We Were Wolves is about trauma and love, and it's about grief, too. Grief is never really resolved. You can't resolve death in any satisfactory way. A loss is never recovered or replaced. So with We Were Wolves I was exploring my feelings in regards to loss and what it means to lose someone, what it means to love a parent.

4. How well do you know your characters before you start to write?

The story began with a single image. It was of a boy of around 15 sitting by a campfire in a clearing in the woods. It's early morning, cold. He's alone. There's a sense of freedom, but of great loss, too, a sense of anxiety. I knew he'd recently lost his father, and the father had been a source of strength to him, but also a burden, an agent of chaos. As he's sitting there, watching the fire, a dog appears to him. The dog is a symbol. It could be freedom, or it could be danger. The boy, sensing all this on a subliminal level, adopts the dog, so he's not alone. That was the scene I imagined. When I finally wrote the story, I changed it so the boy's father was alive but in prison, but the rest of the scene pretty much remained the same.

When I write I very rarely think in visual terms to begin with. My writing and illustration work are very separate disciplines, but occasionally, a short story or novel can grow from an image or the appearance of a character, say. It's usually a scene where a character is at a crossroads, where she or he has a choice to make. It's a bit like when you notice someone on the street who is clearly lost in thought. Their face has a blank expression, but you know it's hiding all sorts of worries and desires and problems, and you wonder what's happened to them today, what's caused them to seem so distracted. Somehow in that expression you find a whole story, their whole personality - or your perception of it.

That's what it's like sometimes when you write. You don't know the character at all. You just have this glimpse of them, and the nuanced, complex expression on their face or the bearing of their body - or you overhear something they say, either to themselves or another character. And that gives you a snapshot of who they are, and what dilemma they are having to contend with. From there you write the next scene and the next, and slowly you get to know them in the same way the reader does.

5. You also bring mental health issues into the story - how did you research this?

I have a pretty wide experience of mental health issues - including trauma, compulsive behaviours, depression, eating disorders - whether it's in my family, or with people I've loved, or my own personal experience. Mental health problems aren't rare. We all know and love someone who needs support, and hopefully we have a greater freedom these days to talk about these issues and be honest about them.

So many children have parents who struggle, and they have to become carers at a very early age. That gets overlooked, and we should be more open about how tough some people's lives are, but how they survive, too, despite it all.

It's not unusual, it's not to be stigmatized or ignored, and it can be celebrated, because people get by, they build families, they work and love and they lead good, happy lives.

6. How did the sense of mythology grow with the story, and why did you decide to bring in these

elements? Do you enjoy reading myths?

The mythology was there from the start - from the first appearance of the dog, Mol, and what she represents to a boy who finds himself alone with no idea how to cope or what he can expect when his father returns from prison.

I spend a lot of time walking in nature. Where I live, I'm surrounded by moorland and woods and fields. I grew up on a council estate in Leeds, but like many estates it was built by brown and greenfield sites, and so the walk to school took us through a fairly large wood. It's almost vanished now, eaten away by business parks and industrial estates and by the quarry at its centre. But back then you could walk in every direction for an hour or so.

It was that wood I pictured when writing We Were Wolves. When you make that journey in memory, it's very easy to fall back into the imagination of your younger self, back when nature was everywhere, and it was safe. It was the people outside, and the noise of cars or the appearance of strangers in the woods that posed the danger. I wanted John, the father, to find safety and peace in nature. He's a man out of time. He's in conflict with the modern world, and would have probably been happier living centuries ago.

In the woods, he can imagine a greater peace, an ancient land where creatures that are now extinct might live again. He's mourning the man he was, perhaps, when he was younger, and that sense of mourning is imposed upon the world that has changed around him. He has a hunger for a greater authenticity - an authenticity he can find in the trees and the soil. The boy embraces these ideas, and because he admires and loves John so much, he actually begins to see these creatures. He imagines wolves in amongst the trees. And the wolves are him and John, of course, both in danger of becoming extinct.

One of the first illustrated books I fell in love with when I was young was by Alan Lee and Brian Froud, called Faeries, which played with lots of old English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh myths and legends. I read the Mabinogion, and Scandinavian myths and read all I could about fantastical monsters and creatures. People have always had a need to create stories that somehow illustrate inner conflicts and fears, and myths provide an outlet. I've always loved William Blake's paintings and poetry, who created his own very complicated religious-based symbolism, and it seemed natural that John, although an atheist, would have a strong kinship with an eccentric visionary like Blake.

7. The illustrations are wonderful in supporting the text. Why did you decide that you wanted illustrations in a book for teenagers? Is there any other illustrated fiction that stands out for you?

We Were Wolves was written with no intention of being an illustrated book, and the idea only arose when I was having conversations with publishers. Initially I was resistant to the idea, but I've always loved black and white artwork. It's my favoured form of illustration. That's all I did when I was a teenager - making pictures with ink and dip pens and brushes, and creating new textures and patterns.

I thought I could go back to those techniques to depict the organic world where John and the boy live. The story is a mix of the natural world and the world of men, the natural and urban. The quarry at the heart of the woodland - which is something I experienced in my childhood - is the perfect symbol of that. That makes an interesting juxtaposition, visually. I wanted to explore that, and tip my hat to illustrators I've always admired, like Harry Clarke, Arthur Rackham, Charles Keeping, Dave McKean, and comic illustrators such as Mike McMahon and Bernie Wrightson.

When I wasn't playing football and hiding in woods as a kid, I was reading comics, so there are small tributes to all those great artists in the work. I also love wordless picture books, block print books from last century such as Franz Masareel's Passionate Journey, and Lawrence Hyde's Southern Cross.

8. How did you approach the illustrations, did you begin these as you were writing?

Once Charlie Sheppard at Andersen acquired the book, we had our initial conversations about story and presentation, then I went away and worked on some sample illustrations - images of the wolves of the boy's imagination, a confrontation in the woods, the caravan by the stream. I completed a few of these before beginning work with the designer, Jack Noel, who slotted them neatly into the layout. We then agreed which scenes were essential to depict, and I began drawing.

I started with pencil drawings and then worked them up with ink and a selection of different nibs and pens, adding washes and broader brushstrokes. I then scanned it all, and rendered the rest of the image in Photoshop with handmade textures and patterns. I was given a lot of freedom in how I rendered the work.

It was a supremely enjoyable working process, and I can only thank everyone at Andersen for their enthusiasm and skill in producing the book with me.

9. Other than an enticing read, what would you like readers to find in this story?

I'd just be glad if anyone read it. We all have so many demands on our attention that for someone to pick up the book and read it and enjoy it, is more than enough. Even though it isn't autobiographical, We Were Wolves is a very personal story for me, given the themes.

There aren't that many books that focus on the love between father and son. I remember reading Dahl's Danny, The Champion Of The World when I was a boy, and not liking it because it didn't have the malicious cruelty of Dahl's other books. When I picked it up later, as an adult, I found it touching and unusually warm. If a reader found the love at the centre of We Were Wolves similarly touching, I'd feel very lucky.

10. Where was this book written, and where and when do you do your best writing? Any bad writing habits?

I understand compulsive behaviour and how habits can become restrictive rather than freeing, so I try not to have set routines about how, when or where I write. I've always been very disciplined, but I've never set myself a goal of writing so many words a day. I get up and I work, every day, and stop working in the evening. That's pretty much the extent of my routine. Any writing is productive. If you realise that a day's passed and you just have a single sentence to show for it, that's enough. Even if you know you'll edit it out in the next draft. Nothing is in vain, it all adds to what you're developing - the story, the characters. Writing is about making choices, and sometimes you have to make bad choices before you know what direction you're supposed to be going in.

I honestly can't remember where I wrote We Were Wolves, but I imagine it was mainly at my desk at home. I can guarantee some of it was written elsewhere however. Writing is simply something I do, and have always done, so there is no work schedule as such. It's part of life.

I write everywhere I can - on trains, planes, in the car, in a field. In times past, like most writers I know, I enjoyed going to a café or a library to work, but clearly in the last year that hasn't been so easy. Libraries are essential to a society, essential in growing children's imagination and knowledge, and they are probably even more significant for adults who missed out on a good education due to the difficult circumstances of their early lives.

I would hope, whether or not we as a society are contending with a pandemic, governments would always deem access to well-funded libraries as a priority. That doesn't seem to be the case currently. If they don't, then our society, our culture is diminished.

11. Are you working on more older / illustrated fiction?

I'm working on a new novel, and reworking drafts of novels, and writing short stories. I'm beginning work on an illustrated book with a US publisher at the moment, and I'm developing another fiction title with Andersen Press.

12. What are your top tips for other young people who want to develop their illustration skills?

If you find that you're spending most of your time drawing or painting or thinking about pictures, then you have a good chance of making a living from it. The same goes for writing. If you read every day, if you find fragments of stories coming to you, you could be a writer. And if teachers accuse you of daydreaming too much, then you're probably not daydreaming enough. Daydream harder. There are no writers who aren't daydreamers.

Keep doing what you're doing, and you'll get better. You can call it practice, but that's a very dry, unattractive word. If you're going to be a writer, you'll write. If you're going to be an artist, you'll draw. It won't be practice, it'll just be what you do every day, naturally, instinctively. Read as much as possible, and look at as many illustrators and artists as possible. Be curious, try new things, and the technique will follow.

Later, you'll go to university, because it's almost impossible now to pursue a career without having some further education. My experience of education was mixed, and I avoided going to art school for as long as I could, but eventually went to Falmouth Art School (now Falmouth University). If you're already applying to illustration or fine art courses, or looking into creative writing courses, then you already know the general direction you're headed and why, I imagine, and don't need much advice, except to hold onto what initially put you on that path, and try to protect that passion, which isn't always easy.

If you're younger and aren't sure whether it's possible to have a career in publishing, I can tell you that it is. It's hard, especially if you lack a family who can support you financially in tough times. It's not easy to make a living, and even harder to sustain a steady income, but you can survive. I have, just about. You can only do that if you're disciplined, and the best discipline comes from a love of art, of technique, of books, of stories.

You're going to have to tap into that enthusiasm when you encounter failure or when doors are closed to you. It's not easy to find a place for yourself in publishing if you come from a working-class background, but you can, with luck. But you'll have to be stubborn and dedicated and be immune to knock backs. I had the privilege of being white, and it's harder if you're a black writer or illustrator or a person of colour. But those writers and illustrators are out there, and publishers really need to finally get rid of the traditional restrictions that stop those creators being published, and champion them as professionals and artists, so stories can be told that reflect the lives and experiences of everyone in our society.

We Were Wolves

We Were Wolves