Poetry as Rebel Writing by Matt Goodfellow

Posted on Thursday, September 23, 2021

Category: Book Blog

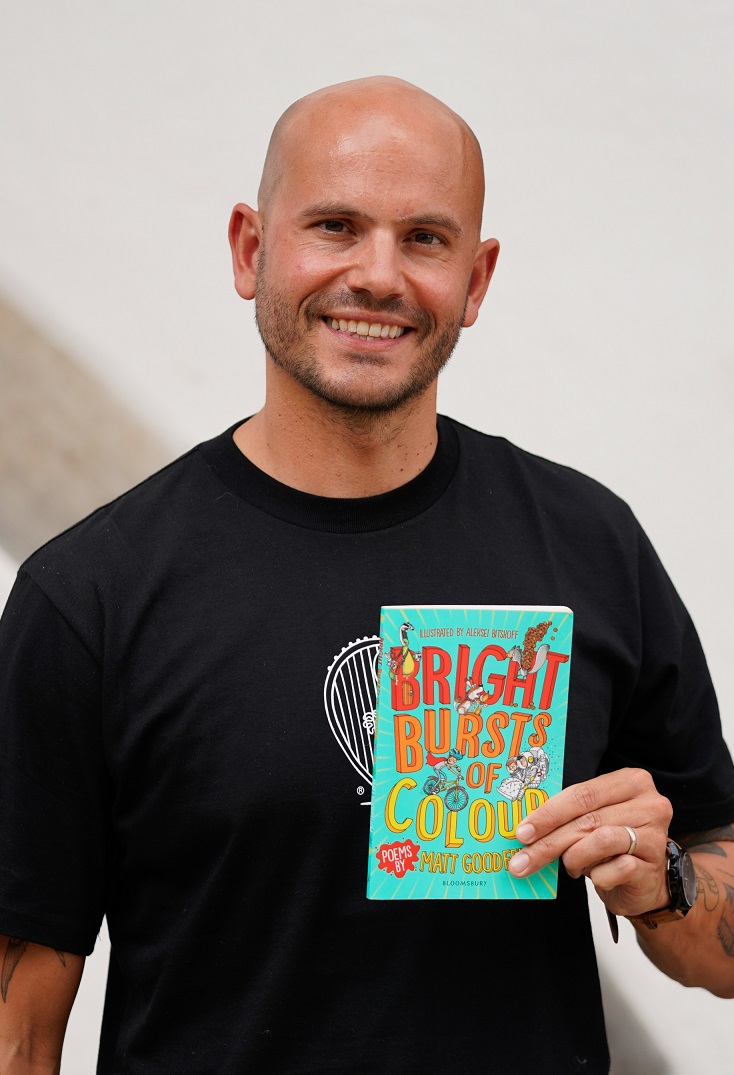

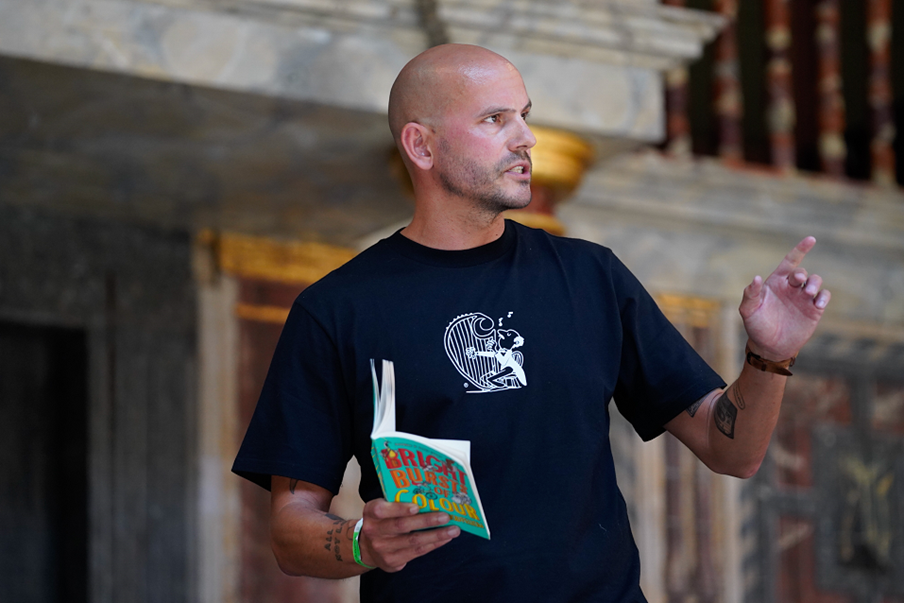

Matt Goodfellow is a poet and performer whose collection, Bright Bursts of Colour, was shortlisted for the CLiPPA poetry award 2021. Here, he blogs about poetry as 'rebel writing' and gives suggestions for introducing poetry to the classroom.

Poetry is a problem. You only have to walk into the children's section of most (not all) bookshops to see it's a marginalised, hidden away and maligned genre of writing - after scrabbling around, sometimes on hand and knees or asking a shop assistant, you'll generally find a handful of poetry books by the same well-known poets and hard-backed, big-budget anthologies nestling next to the joke books on the bottom shelf, tucked well away from the brightly lit tables of 'Buy One Get One Half Price' novels.

Poetry is a problem. When I first became a primary school teacher in 2007, it became clear to me relatively quickly that most (not all) teachers dreaded the couple of weeks of bolted-on poetry they had to teach a couple of times a year - and lost count of the amount of classes that must have been exposed to Kit Wright's (fantastic) The Magic Box as well as Alfred Noyes' (equally fantastic) The Highwayman, plus a few others, as their entire primary school poetry diet.

Poetry is a problem. Having left life as a teacher behind a good few years ago, I now work as a poet in schools, libraries and festivals and am delighted to see the way that reading for pleasure has become centre-stage in lots of classrooms and often see fantastic displays along the lines of '100 Books to Read in Y4' and 'I'm Currently Reading…..' etc, but most (not all) of these have few, if any, poetry books.

So, once more: poetry is a problem. Now, the reasons for this are, in my opinion, far too numerous and knotty to go into in such a short article, and range from certain poems and certain poets/academics consciously or subconsciously exuding an air of elitism: the idea that poetry is only for a gilded, concentrated few, which can make many people feel excluded; all the way through to the suspicion that many teachers and adults carry with them about poetry from the way it was taught in their own school years.

But poetry doesn't need to be a problem. In my mind, yes, it is different from any other kind of writing, but not for any scary reasons: it's rebel writing - it follows no-one's rules, can't be governed or pinned down by age-related expectations or indeed be defined at all, really. Nobody can actually tell you what poetry is.

In my opinion, the best way to demonstrate that poetry can be a magical, mercurial shape-shifter, capable of doing an infinite amount of things, is simply to open as many doorways to it as possible.

The best way I found to do this as a teacher was to read a poem out every day (I set aside that brief moment just before lunchtime when we were tidied away and focused). It's not rocket science and is a well-trumpeted idea which has been championed by many more intelligent people then me many, many times over. Sometimes I'd show the poem under the visualiser so we could discuss and reinforce our growing understanding of the way poets are rebels and can pattern the page with their words however they choose. Sometimes we'd discuss how some poems contain punctuation and some don't; some poems are easy to understand, some aren't; some poems are funny, silly, sad, thoughtful, weird; some poems are written in very posh, archaic language and some are written in normal everyday language, grounded in the poet's own dialect and therefore their cultural heritage - writing in their voice, about their life.

Very quickly the children (and I) began to realise that poetry was not just one thing, and could be relevant to their lives, because they could do the same - they could write down their thoughts, feelings and emotions about life in their voice, about their lives, without needing to worry about any of the strict grammatical controls that govern the rest of the writing curriculum.

When it came to becoming rebel writers, we'd use a poem we'd found and liked in our daily read-aloud sessions - and would spend a couple of lessons just talking about, annotating, and performing that poem: what shapes/patterns did the poet create? Did it rhyme? Did we like the poem? Why? What sort of words did the poet use? Was there any repetition? Punctuation? What did we think the poet might be trying to say? The brilliant thing for a teacher discussing poems with a class is that the expectation of the teacher having all the knowledge and answers simply disappears as none of the above questions have right or wrong answers - the teacher can say 'I don't know, what do you think?' And that is a rebel educator, right there!

Once these initial discussions had taken place, we'd split into groups and start deciding how we might perform the poem: was it loud and rhythmic, needing accompaniment from the dusty music trolley - and big, expressive movements? Or very quiet and gentle, needing a quieter touch?

By the middle of the week, and after our performances had been filmed or shown to other classes, the children would know the 'shape' of the poem inside out - and were very comfortable using that shape as a coat-hanger or starting point to begin to hang their own ideas. I always used free verse as a vehicle for children to tell the truth about their lives so they didn't get pulled away from truth by the pressure of need to find a rhyme (and by this stage, they'd heard so many different kinds of poems, the idea of a poem needing to rhyme had long disappeared).

We'd start off with a shared write, together on the board, with me modelling my own choices as a rebel writer about punctuation and patterns on the page - and we'd create a 'first go' at a class poem - and we'd discuss it. Then children would have a go on their own.

It became incredibly freeing for me as a Y6 teacher to not have to have toolkits or checklists for the children to shoehorn into their writing (I remember my daughter, Daisy, now 11 and at secondary school, coming home one day when she was in Y5 to tell me that she'd been doing poetry and had been taught that all Y5 poems must contain similes and metaphors) - they could focus on writing in their voice about their lives. Rebel writing became a pressure release where they really understood they could write for pleasure and that poetry was the vehicle for that - and I wasn't going to be standing over their shoulder saying: 'Well, that's great, but it's not at age-related expectations yet because it's missing X, Y or Z…' In the last part of the week's sessions, children would get their initial drafts shaped into a poem that was right for them, that looked how they wanted and sounded how they wanted - a genuine piece of rebel writing in their voice, about their life.

Poetry is a problem, but it doesn't need to be.