Debi Gliori

About Author

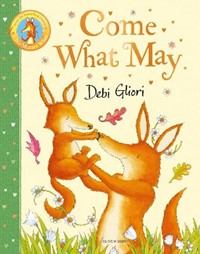

Come What May, Debi Gliori's reassuring and warm picture book about familial love, returns the reader to the world of No Matter What, and the characters Large and Small.

Debi has created over 80 books for children, including the bestselling No Matter What (Bloomsbury) and the Mr Bear series (Orchard), and has sold over 500,000 books in the UK alone.

She lives near Edinburgh and trained at Edinburgh College of Art. Inspiration for her books has come from watching and listening to her children; she says 'most of what I do is based on and around their lives and dreams and hopes'. Debi works from a studio in her back garden and also loves cooking and gardening.

Interview

Debi Gliori explores big feelings and questions in 'Come What May' (Bloomsbury Children's Books)

March 2025

In this warmly reassuring story of love between an adult and child, Debi Gliori returns to the characters, Large and Small, who we first met in her bestselling picture book, No Matter What. In Come What May, Small once again struggles with big feelings but learns that whatever happens in their life, they will always be loved.

In this month's feature, Debi Gliori explains how the original story, No Matter What, came about, why she wanted to revisit Large and Small in a new story, and why she feels the the stories have hit a chord with young children and their families.

Q&A with Debi Gliori: Exploring big feelings with Large and Small in 'Come What May'

"Large's repeated assertion that come what may, no matter what, she'll always love Small is deeply reassuring,

but that reassurance is amplified by Large's references to the immensity of the natural world."

1. How did you first start in children's illustration and writing, and what drew you to picture books? What have been your career highlights so far?

I spent a very happy five years at Edinburgh College of Art studying illustration and design with Harry More-Gordon. It never occurred to me to want to do anything other than picture books; they're such a perfect home for illustrators to explore and mine the range of their imaginations.

Every time I can actually get the images in my head out onto paper without my inner critic getting in the way is a moment of bliss. Not sure if that's what you mean by a career highlight, but since 95% of my working life is spent on my own, wrestling with paints and charcoal, such moments of creative success are, for me, highlights.

2. What inspired your first picture book, No Matter What, about parent and toddler Small and Large?

I wrote it to try to comfort my eldest daughter, whose life was turned upside down when her dad and I separated. Rather than try to explain the ins and outs of why her dad and I had taken such a disruptive decision, I tried to show her that no matter how she behaved, or what she said or did in her understandable hurt and confusion, I would always love her.

3. How did you first develop these characters and their look?

So much of the thinking behind 'No Matter What' was intuitive. I was desperate to help my child in any way possible. I didn't want to illustrate Large and Small as two humans - I've learned that when I'm dealing with big, emotive subjects in my work, it's often easier on the child reader if there's an indirect reference to the big emotive stuff. A kind of protective layer.

So, rather than making it a book about divorce with a human mummy and daddy, I made it a book about big feelings that we can struggle to contain. I drew Small first (of course) and I didn't even think much about what manner of creatures Large and Small would be. It was an intuitive leap of faith to make them foxes.

4. Why did you want to return to Small and Large and the love they share with a new story, Come What May?

No Matter What came out of a very difficult period of my life. I think I was possibly comforting myself alongside my daughter when I wrote it. Twenty years had passed since writing it and the subject of a follow-up book came up frequently in discussions with the team at Bloomsbury. I wasn't at all keen to write another Large and Small book. I think that because No Matter What came from such a place of upset and hurt and was made in a state of such emotional intensity, I didn't want to dilute the emotional weight of it by writing another, lesser story from a place of less emotional intensity.

And then, in 2020, came the pandemic. The news from all over the world was frankly, terrifying. Being of a deeply anxious disposition, I was struggling to contain my terror at the prospect of…what? Nobody knew for sure. Publishing ground to a halt. The book I was about to hand in (The Boy and the Moonimal) went into a holding pattern. My youngest daughter packed up her flat and came back home to shelter with us. Apparently, as a nation, we ran out of toilet paper! Suddenly life as I knew it was over.

For a while, back in the initial weeks of lockdown, despite the exquisite spring weather, I was wondering if we were seeing the end of the entire human project. To attempt to calm myself down so that I could actually function, I would go out for a run early in the morning before there was any possibility of encountering other potentially infectious people.

In the silence (remember how still and quiet it was without cars and airplanes?) all I could hear was birdsong and the steam engine huffing of my breath and the thud-thud of my feet. A rhythm of sorts. And in that rhythm under the benign presence of blue skies and unfurling leaves, words came into my head. 'And everything will be ok, we'll always love you, come what may.' And I knew that Large and Small were back, their timing impeccable, their presence in my thoughts so very welcome.

5. What did you want to explore in each of these stories, and how do the stories help to reassure young children?

I think both books are about how big feelings can sweep us away by their strength. Small children can get to a place where they're so consumed by their feelings that they are literally 'beside themselves'. The strength of their emotions has almost engendered an out-of-body experience. One part of them is aware of how unlovable they've become and the other part is incapable of doing anything to change that. And that's terrifying for a small person.

To lose the love of a parent? That's one of the worst things imaginable. So Large's repeated assertion that come what may, no matter what, she'll always love Small is deeply reassuring, but that reassurance is amplified by Large's references to the immensity of the natural world as evidence of the immutability of her love.

6. What kinds of follow-up discussions or activities can you suggest for adults to share with young children after reading these picture books with them?

I would hesitate to suggest anything - that's entirely up to the individual families. I feel as if I've dropped my pebble into their pool, and I don't feel qualified to start directing the ripples that spread out from the centre. The books will 'land' in a thousand different ways in each family and with each reading.

When I speak to parents at book festivals, they tell me their stories about what 'No Matter What' has meant to their families. Many of these stories are profoundly moving. I invariably feel honoured beyond my ability to frame in words at how my words and pictures have been taken into so many hearts and lives across the world. And I do cry, frequently, when I hear how such connections have come about.

7. Did you need to revisit No Matter What in detail when you created the voice and world for Come What May? What makes the books so distinctive?

Not for the voice, but I did need to make sure that the world Small and Large inhabit in Come What May was recognisable as the same world in No Matter What. Because I take my foxes outside in Come What May, I had to draw myself a map to make sure the view from the windows and doors of No Matter What was correctly aligned with the landscape that Large and Small explore in Come What May. This proved to be quite difficult, especially for this left-handed illustrator with my innate inability to read real maps without a major struggle.

8. Where do you start when you're developing the images for your picture books, and what process do you use to create your images?

Once I have the story in a form that I'm happy with, I'll divide it up into pages, paying attention to maximising the effect of where each page-turn will occur. Then I make rough pencil sketches, in no particular order, simply trying to feel my way into my characters. I play around with some of their poses, paying particular attention to the body language of each character and how their hands, the placement of their heads, the articulation of various parts of their bodies best expresses what their feelings may be.

Once I've made enough little scribbly sketches to feel that I'm ready to begin laying out the pages, I'll measure out several same size sheets of layout paper, mark them up with ink borders corresponding to the exact size of a double page spread, and then begin. I make lots of tiny thumbnail sketches round the perimeter of the layouts, working and thinking and dreaming and generally trying my hardest to not get in the way of myself until I have nailed exactly what I'm trying to say. Then I'll draw the spread, adding details, shadows and rough placement of text. This is all in black and white.

Once I'm happy, I'll submit this set of rough drawings to my editor and designer at Bloomsbury. We work as a team to turn my ideas into as coherent and perfect a book as possible. Usually, there are revisions, sometimes many, many revisions; places where the illustrations could do more of the heavy lifting, places where I've inadvertently repeated a view or have failed to advance the action, or just generally have been so close to the drawings that I've lost the ability to actually 'see' them clearly. This stage can take a very long time.

Historical note: the original No Matter What roughs didn't go through such a rigorous filter; the text and the images were exactly as I wrote and drew them first time round. The finished book was the same version I'd written and drawn at the first draft / first rough drawing stage. This kind of miraculous straight-from-head-to-publication journey rarely, if ever, happens nowadays. I'd be lying if I said I prefer the present-day system, but I do respect the need for such a process.

Once we're all happy with the revisions, it's time to stretch sheets of cold-pressed 100% rag watercolour paper onto wooden boards (to stop the paper buckling with the application of watercolour washes) and begin painting. Sometimes I'll multitask and listen to music or an audiobook, sometimes I feel the work requires my absolute and undivided attention and I'll paint in silence.

9. Can you tell us how you develop the humour and details in the images, bringing Small and Large's world to life?

It's all about immersion. I'm living in Large and Small's house as I draw them. I'm imagining life as a fox. Obviously, an extremely protected, anthropomorphised and idyllic fox-life, but sufficiently foxy for Large and Small to not be vegetarians.

There are details from my real life in there - the landscape isn't Scottish, so much as a little corner of Caledonia that is forever Tuscan. The distant coast, the lines of poplars, the thicket of foxgloves, these are all places I've seen, or briefly inhabited, but putting them all together for Large and Small is my gift to them ( and myself). Their little wonky house? Clearly that comes from my inability to draw with any degree of architectural verisimilitude, alas.

The house interior, apart from being a complete Tardis, is wish fulfilment writ large (I'd love to have Large's wood burner, or her glorious tiled cooker). Small's hat? Well, I am a very dedicated knitter, so it makes sense for Small to wear a hat that looked decidedly homespun. Their pictures and posters on their walls, and their fabrics and wallpaper are all fox-related. The diagram in the kitchen in No Matter What about how to break into wheelie bin and bin-bags? That's what foxes do, so it makes sense that they'd celebrate the technique in a poster. There's a limited edition print in their living room showing a little rabbit surrounded by a few ingredients for Cassoulet de Lapin… I think a little darkness helps us appreciate the light. My foxes are still foxes, after all.

10. Are there particular spreads or parts of the text that stand out for you in Come What May?

I have a particular fondness for Large's expression as she reassures her insect Small while both are tucked up inside a foxglove blossom. Her love is so obvious and her expression so tender. Given that the entire emotion is riding on the precise placement of approximately 3mm of ink, you can imagine how much focus I had to bring to bear on the moment I actually inked Large's eye in place.

This was the second time I'd painted this spread in full. First time round, the foxglove was cream (in the book, it's purple) and because I am a totally analogue illustrator, I couldn't select the area with a cursor and digitally recolour it with a series of adept 'clicks'. ALAS! For me, it's many day's work discarded and start again. Failing better, I believe.

I also love, love, love the very last spread. I had no idea what it was going to be until I roughed it out and its echoing and magnifying and completing a circle with No Matter What was one of the highlights of my working life. Ah! I've really answered your first question about career highlights here. A little moment of spark.

11. Do you have any more stories planned for Small and Large?

I have no more stories planned for Small and Large, but if they return to tug at my sleeve, I'd be overjoyed. To return to their world with Come What May, and to discover that they'd been there all along, for the past 25 years, not exactly waiting, but quietly confident that I'd find my way back was astounding. And heart-warming. And utterly joyous.

12. Are you working on any projects currently?

Yes, a new book about Dr Purr, a retired doctor-cat who hopes to put her paws up, practise her fiddle and never have to prescribe a pill ever again. Needless to say, this doesn't go according to plan. I've just sent the first set of roughs to Team Bloomsbury and am really looking forward to the process of turning this into a book.

Also, I'm in the very early stages of a gloriously vast picture book/anthology project I've been mulling over for several years. It's at such a wispy, nebulous stage that I prefer to not try to describe it here. I've pitched it to my lovely editor at Bloomsbury and I've gone and bought it a very workwomanlike square Leuchtturm sketchbook to give it a home to grow in. Suffice to say, it's the very last thing I think about before I go to sleep and it's the first thing I think about when I wake. This dreaming stage is amazing; it's one in which I frequently stumble across little serendipitous 'signposts' in my daily life, little pointers that nudge me back to focusing on the wispy project and offer evidence that I'm on the right track. Whatever 'track' that is. She said, wispily.

I'm currently writing a weekly newsletter on Substack all about my process with new book projects plus occasional essays where I go through some of my eighty-odd published picture books and write about where they came from and how I made them. I am really enjoying the connection with readers and other illustrators and artists. And unlike every other platform I've tried, posting on Substack doesn't render me sobbing with digitally thwarted frustration. I can make it work. Mostly.

13. Can you describe your studio, where you do your picture book work?

It's a bit of what we call in Scotland, a ‘midden'. Meaning the compost pile/rubbish dump out of which great things can come. Scara Brae on Orkney was dug out of a prehistoric midden, and emerged in a state of astounding preservation, thousands of years past its creation.

So, I work in a creative midden, surrounded by so much paper that wasps have moved in and built a nest somewhere in the eaves, clearly delighted by the proximity to limitless supplies of building materials. It's a garden shedquarters, originally sited in a beautiful walled garden where my partner once was head gardener/estate manager. When we moved, I had the studio de-constructed and transported in bits to be reassembled in the business end of our small garden. By business end, I mean next to the compost bins, woodsheds, log-processing sawdust mountain and falling-down greenhouse. All salutary places to contemplate as you attempt to create timeless, eternal works of children's fiction.

Somehow my studio accommodates my bicycle, a plan chest, a wraparound desk, a long table salvaged from a village hall, an old kitchen credenza, a proper stand-up painter's easel and my salvaged architect's drawing board. Windows all round and two very leaky skylights to maximise light. Hundreds of books on a rather perilously tilted shelf. A space in the rafters where bits of paper and old portfolios go to die. I haven't investigated what's actually up there for decades. Actually, I haven't washed the floor for just as long. I know… but there simply aren't enough hours in a day. Fortunately I'm the only person who sees it.

At the moment, with one thing and another, I can't justify the expense of heating it through the winter and after many late autumn days of layering increasing numbers of hand knitted jumpers one on top of the other until I'm about as rotund as the Michelin Man, I give up and retreat indoors to the house. Till the weather warms up again.

14. What do you enjoy doing or creating when you're away from your studio, and what takes your mind away from thinking about stories?

Nothing takes my mind away from creating stories. Those synaptic pathways are so baked into my everyday functioning that I can't find the dividing line between where the life I'm living ends and where they start. However, there's a kind of creative continuum that I mine for all its worth. The process of making my books overlaps and flows into playing music with friends, into knitting and designing elaborate projects, into going out on my bike to allow ideas the space to blossom, into hillwalking and sea-swimming to nudge a creative congestion back into a state of flow. It's all one thing, indivisible and immensely nourishing and mysterious at the same time.

Come What May

Come What May

No Matter What: The Anniversary Edition

No Matter What: The Anniversary Edition

The Bookworm

The Bookworm