Nick Crumpton & Gavin Scott

About Author

Dr Nick Crumpton's new book, Everything You Know About Sharks is Wrong gives us a close-up look at the world of sharks.

Nick Crumpton grew up on a diet of David Attenborough documentaries, studied ecology at Leeds University, and went on to work at the BBC Natural History Unit; the Natural History Museum, London and the Zoological Society, London. When not writing books, he works as a zoological consultant. www.nickcrumpton.com

Illustrator Gavin Scott grew up in the Dorset countryside where, as a young child, he loved to draw grass snakes or other interesting creatures. Gavin studied Natural History Illustration at University and now works in character design and children's illustration.

Interview

Everything You Know About Sharks is Wrong (Nosy Crow)

June 2023

"A book about sharks was clearly a must. I'd be hard pressed to think of another group of animals so villainised by so broad a group of people across so many cultures."

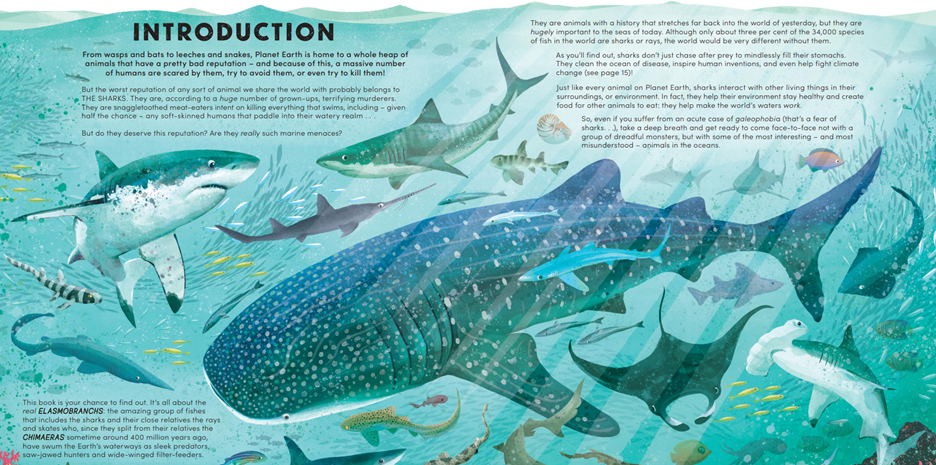

Sharks are giant, cold-blooded creatures that enjoy eating humans, right? Well, this book is here to show you that you're WRONG! There is so much more to learn about these incredible creatures and in this new book by biologist and author Nick Crumpton and illustrator Gavin Scott, you'll discover just how smart sharks are, how some sharks help keep the planet cool, what sharks really want to eat - and why they are so important for our oceans!

Nick Crumpton and Gavin Scott tell us more about their research into sharks and question everything you've ever been told about them in Everything You Know About Sharks is Wrong!

See also: Everything You Know About Dinosaurs is Wrong Everything You Know About Minibeasts is Wrong

Q&A with author Nick Crumpton & illustrator Gavin Scott

Q&A with Nick Crumpton

1. How did you start writing for children, and what inspired your first 'Everything You Know About...' book?

I started writing for children during my PhD studies. It was the perfect outlet for my curiosity and love of outreach and engagement (I was always far more interested in what my peers were researching than what I was supposed to be working on… ) and I loved talking to children about natural history.

The Everything You Know is Wrong books came directly out of my experiences speaking at Museum open days and Science festivals, when I began to notice that myths and misinformation were stubbornly sticking around through generations. Although I was keen at these events to showcase new science and new research, it was the most interesting when I challenged firmly held beliefs (I use the word very specifically) and revealed reality.

To begin with, the series just had to begin with a quagmire of untruths: dinosaurs, with Everything You Know About Dinosaurs is Wrong. After that book, which dispelled myths but also introduced the mechanisms of science, Everything You Know About Minibeasts is Wrong introduced the bewildering world of insect biodiversity.

2. Why have you chosen to write about sharks in this new book?

From the inception of the series, a book about sharks was clearly a must. I'd be hard pressed to think of another group of animals so villainised by so broad a group of people across so many cultures. Yet this is a horrendously over-killed superorder of fish that are astonishingly more diverse in both their looks and their behaviours than most people give them credit for. I only wish we'd had space to feature all 500-ish species of shark just to showcase their variety.

3. How much did you know about sharks before you started to write this book - and what most surprised you in your research for the book?

In comparison to my knowledge of other vertebrates, not as much as I should have done. I'm very lucky to know folks including writers like Helen Scales and researchers like Dareen Almoji who've been inspirational in terms of my understanding of the oceans, and working at the Natural History Museum, you sort of absorb knowledge from those around you, but there were so many gaps in my knowledge when it came to sharks. That's what made researching this particular book such an exciting process: it was so much fun to read so much - and discover a huge amount about animals I was aware of but didn't KNOW.

There's a bit of advice when it comes to writing, which is not to write too close to home, and my surprise during the research for this book hopefully comes across in the text. I'm pretty nuts about elasmobranchs these days and I'm really proud there are some facts (and even some species) that were only discovered as I was writing the book - for instance, we're sure this is the first book in the world to feature the newly discovered mesozoic long-finned Aquilolamna.

4. Where did you go to find out more? How 'close up' have you been with real sharks?

For books like the Everything You Know is Wrong series, most of my research is library-based, and I'm lucky enough to use the NHM library in London as well as usual academic research channels. I was also fortunate in that marine biologists like Amani Webber-Schultz and David Shiffman kindly offered their time to answer my (probably very dumb) questions: these are scientists who spend their days around sharks, which I'm afraid I have never done (although there are many shark experts who have never gone diving with their species of choice, and there are very good reasons why not!).

The closest I've been to my favourite species is during a research trip to Oceanogràfic in Valencia, from which there is a photograph of me looking ludicrously happy posing near a zebra shark (one of the prettiest sharks in the world).

5. What are your top 3 Shark Facts? And if you could meet any shark in real life, which one would it be?

Three is hard! But I guess I love the fact that some sharks can undergo parthenogenesis (or 'virgin births') with females giving birth to clones of themselves without any need for a male shark; that megalodon used to hunt whales; and that sharks are smart - lemon sharks have even been trained in the past to push buttons or ring bells to receive treats.

As for meeting sharks, I'm afraid it really must be the classic: the whale shark!

"An almost unbelievable 100 million sharks are killed by humans due to targeted,

unsustainable hunting and industrial bycatch"

6. Has your view of sharks changed in the course of writing this book? What do you most want people to know about sharks?

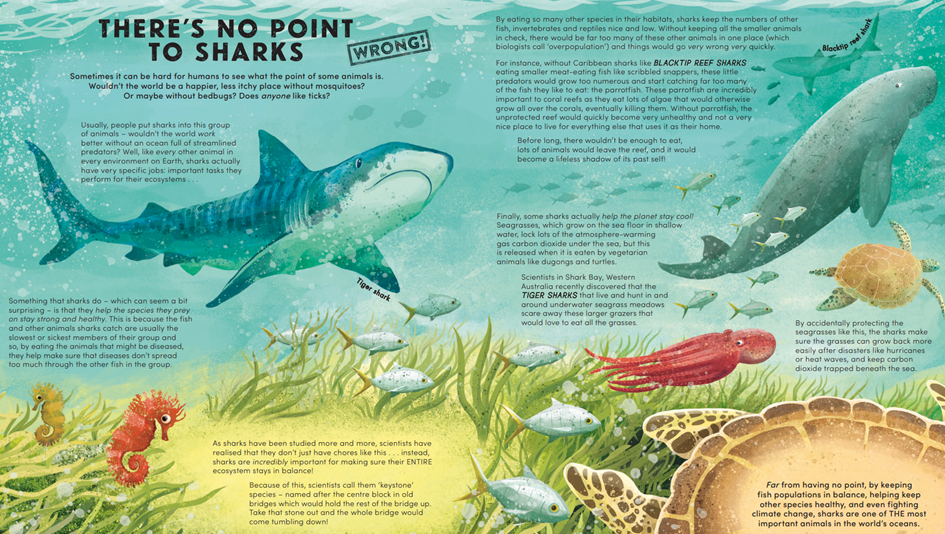

Absolutely. My academic background is in ecology and ecomorphology, so I knew of them as critical elements in their marine ecosystems and as beautifully adapted predators, but their sheer range of lifestyles and habitats was extraordinary to discover.

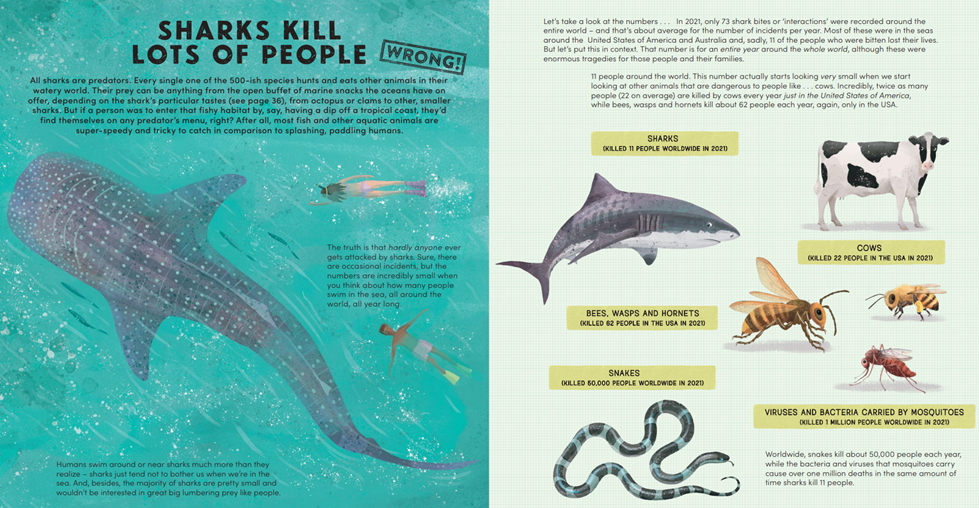

As for what do I want people to know, that's easy. I want them to know that each year more people are killed by cows just in the USA than by all species of sharks throughout the whole world, and that in the same amount of time an almost unbelievable 100 million sharks are killed by humans due to targeted, unsustainable hunting and industrial bycatch.

7. If there is one change we can make to help sharks the most, what would it be?

How about three: if you eat fish, consider how it is caught and whether this minimises the impact on shark populations; write to your MP about implementing protected marine areas; and try to challenge friends and family members' prejudices when it comes to an amazing group of species that have been mercilessly targeted as the scapegoats of the oceans.

8. What do you think of Gavin Scott's illustrations for this book? Are you involved at all in the illustration process?

I was so pleased when Nosy Crow teamed Gavin and myself up together for Everything You Know About Dinosaurs is Wrong. At the time I didn't see how he could create anything that looked better, but Everything You Know About Sharks is Wrong has some breathtaking spreads. He has an incredible gift for marrying anatomical accuracy with child-friendly personalities and the sharks in this book are just beautiful.

We have a great working relationship and I have complete confidence in his abilities, but occasionally we discuss behaviour or shapes after the pencil stage. I love his hammerheads in this book, although his dwarf lantern shark is particularly sweet.

9. Where would you recommend children go to find out more about sharks?

Firstly, their local library! Then they should check out the Shark Trust's website which has some really nice animations and fact files.

Q&A with Gavin Scott

1. How did you become an illustrator, and why did you want to illustrate non fiction?

When I was at school I didn't really know illustration was job that ordinary people could do. Art was my favourite subject though, so I continued it at A level. I then went on to study natural history illustration at art college because it combined the two things I really loved - nature and art.

At art college I worked on some live projects, including information boards for the National Trust's nature reserves. When I graduated, I began working on character design and then went into (fiction) children's books, which I'd always wanted to do. Strangely, the real non fiction work came later when I decided I wanted to get back to more information based illustration. So, I tailored some new portfolio work towards non fiction/natural history in a slightly new style.

As an illustrator, it's really important to be self motivated and if you're keen to do new things you have to work on your portfolio and get it out there. I love trying out new looks and ways of working. My work now is a combination of all the things I've learnt in these different areas of illustration. I still work on fiction books and I also design soft toys, which is really fun.

2. Which of the three books in the Everything You Know About series has been the most difficult to illustrate? Do you have a favourite from among the three books?

I'd say the most difficult, although still really enjoyable, was Minibeasts. This is because bugs and insects are made up of quite a few body parts! Creatures like centipedes have sooo many segments and legs!

I think maybe Sharks was my favourite to work on, but maybe that's because it was the most recent? There is something very beautiful and refined about the shape of sharks. They are just such beautiful animals. Also, the patterns and colouration of some sharks, like carpet sharks and epaulette sharks, are incredible. So much fun to illustrate!

Everything You Know About Dinosaurs Is Wrong was also absolutely incredible to work on and sooo much fun. Looking back on it now I would probably illustrate some things differently - but then I always think that!

3. What did you think the challenges would be in illustrating a book about sharks? Were you correct or did you find new challenges as you started work on the book?

I thought that close up illustrations of sharks, showing their jaws and teeth might me problematic. Obviously, sharks have a lot of teeth! This ended up being partly true, but most sharks don't swim about with all their teeth showing, although they are more prominent on some sharks. I also thought the rays would be tricky, as I like to inject some personality into the animals' features. Rays mouthparts are underneath, so you don't really see them. It was ok in the end though.

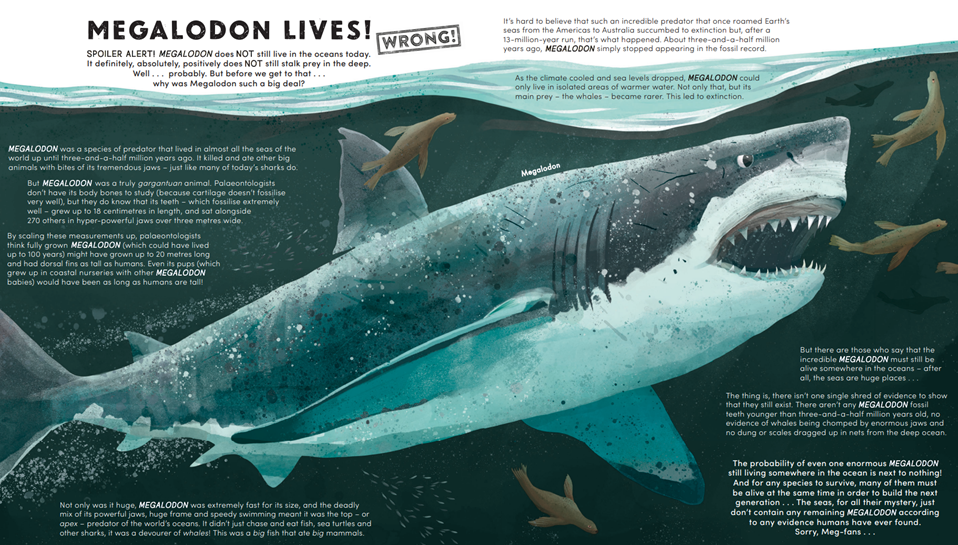

Getting hold of reference for the extinct sharks was quite difficult. As with most extinct animals, the process of reconstructing what they looked like takes a bit of guess work, and new scientific research often changes old ideas and assumptions. Sharks and Rays are particularly difficult to reconstruct, as their bones don't fossilise very well due to being made of cartilage. Often, all there is to go on are teeth and sometimes jaws.

With something like Megalodon, all we really know is that it was a really big shark, eating big things to have big teeth like that! Scientists study the teeth and compare them to animals living today, to get a pretty good estimate of their actual size. I tried to get the newest information I could find, which was the whole ethos behind Nick's writing too. Information in books like this is constantly changing and being revised, so it will always be out of date at some point! But that's the fun with science, right?!

Interestingly, it was formerly thought that Megalodon was a really close relative of Great Whites in the family Lamnidae, but now scientists think that it belongs to a slightly different (extinct) family of sharks called Otodontidae.

4. Where did you go to research sharks for these illustrations, including their habitats?

Well, mostly images and information online. There is just so much photographic reference available. Images of some sharks were quite hard to get hold of though. Megamouth, particularly, is quite a secretive shark and rarely photographed. Incredibly, this 5m shark was only discovered in 1976! Reference was quite thin on the ground, and photographs of caught ones (ie.out of water) look totally different from a swimming Megamouth shark. I also watched a lot of videos of Great Whites hunting and breaching , as I wanted that page to look as natural as possible.

5. What surprised you the most in the information about sharks from this book?

I think what surprised me most was just how intelligent some sharks are. We have a false idea that they are somehow incredibly primitive. Biologists have studied some species of shark playing with toys, doing tricks to win treats, and generally acting a bit like your pet dog!

6. How do you create your illustrations for these books?

I start by collecting all my reference and then arranging shapes around the text on the spread, to get get the overall composition. I tend not to draw as much these days. Instead, it's more like a collage. This is created in Adobe Photoshop on my computer. It's the much the same as creating a traditional painting or collage, except there is more flexibility to edit and try things out to see if they work.

At art college I mainly learned to paint and illustrate traditionally, with only a small amount of work on the computer. Most of what I've learnt to do digitally has been self taught. I then build up the detail gradually. Sometimes spreads will got through several changes of colour before I settle on the final one. Often I end up with several versions and can then decide between them.

7. Which spreads are you happiest with?

I really loved the Rays spread, for it's colours. I also really enjoyed coming up with the composition for that one. The Megalodon spread was also really fun because of the drama of the image. The thought of being chased by a giant Megalodon would be pretty terrifying! Having the shark's tail partly cropped off the page helped to give an impression of size, and also speed, kind of like the shark has entered the scene…but not fully, and will then swim out of shot on the other page.

8. What other kinds of illustration work do you enjoy doing?

Along with the fiction children's books, character design, and toy design, I create linocut prints. I'd like to do more of these but the illustration is taking priority for the time being! I like do create traditional collages too.

Everything You Know About Sharks is Wrong!

Everything You Know About Sharks is Wrong!

Everything You Know About Minibeasts is Wrong!

Everything You Know About Minibeasts is Wrong!

Everything You Know About Dinosaurs is Wrong!

Everything You Know About Dinosaurs is Wrong!